Removal of biological organics in high-salinity wastewater produced from methylcellulose production and subsequent changes in the microbial community

Article information

Abstract

The wastewater generated in methylcellulose (MC) production is characterized by high salinity and pH due to the residual sodium and chlorine separated from the methyl group. It is difficult to treat wastewater using the conventional activated sludge method because the high concentration of salt interferes with the microbial activity. This study confirms the biological removal of organic matter from MC wastewater using sludge dominated by Halomonas spp., a halophilic microorganism. The influent was mixed with MC wastewater and epichlorohydrin (ECH) wastewater in a 1:9 ratio and operated using a sequencing batch reactor with a hydraulic retention time of 27.8 d based on the MC wastewater. The removal efficiency of chemical oxygen demand (COD) increased from 80.4% to 93.5%, and removal efficiency had improved by adding nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus to the wastewater. In terms of microbial community change, Halomonas spp. decreased from 43.26% to 0.11%, whereas Marinobacter spp. and Methylophaga spp. increased from 0.50% to 15.12% and 7.51%, respectively.

1. Introduction

Although cellulose is a widely used natural polymer material, its use is limited due to its low solubility. Cellulose derivatives have been studied to address this issue and expand the scope of applications. In particular, methylcellulose (MC) is a cellulose derivative that resolves the insoluble properties of cellulose in organic and inorganic solvents, and has recently been used in diverse industrial applications such as food, petrochemicals, and building materials [1–3].

MC wastewater is characterized by high levels of salinity and organic matter. During MC production, chloride ions are separated from chloromethane and sodium ions separated from sodium hydroxide are discharged as wastewater [4, 5]. In addition, MC production involves the addition of a plasticizer (propylene glycol) and solvent (1-methoxy-2-propanol) [6], and the chemical oxygen demand (COD) concentration in the wastewater is increased by residual plasticizers and solvents.

High concentrations of salt affect biological activity in the conventional activated sludge process [7], in which microorganisms have a high osmotic pressure in their cells. High osmotic pressure can lead to the dehydration and degradation of cells and inhibit the growth and activity of microorganisms [8]. However, halophiles are known to dominate highly saline conditions and have the capacity to remove organic compounds without inhibition [9–13].

Although research on MC wastewater treatment has confirmed the potential to substitute an external carbon source necessary for denitrification [14], there is insufficient research compared to other cellulose-based wastewaters. A study on carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) wastewater treatment, a cellulose ether (carboxy alkyl series) similar to MC, was conducted using a physicochemical treatment method [15, 16] and a physicochemical-biological mixing method [17, 18]. Although these studies demonstrated effective organic matter removal, each of the physicochemical treatments used had the disadvantage of high energy consumption [16, 19].

Petrochemical and food processing wastewaters are similar to MC wastewater with high salt and organic content [20, 21]. High-salt wastewater is treated in parallel with physical and chemical treatments [20, 22, 23], at great expense and energy expenditure [7]. Although studies using anaerobic sequencing batch biofilm reactors (AnSBBR) and membrane bioreactors (MBR) require lower cost and energy consumption compared to physicochemical treatments [24, 21], extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) released by microorganisms at high salt concentrations exhibit sub-optimal performance of the membrane (biofilm and membrane) [25, 26].

Other studies have applied several physicochemical methods such as cohesion, distillation, photocatalysts, and membranes [15–18, 20, 22–24]. However, there has been an absence of studies demonstrating the removal of COD from MC wastewater using biological methods. The purpose of this study was to remove the COD of MC wastewater through a biological method under highly saline conditions using sludge dominated by halophiles. In this study, we aimed to identify the microbial community changes through pyrosequencing and provide useful insights into MC wastewater treatment.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Properties and Characteristics of the Wastewater

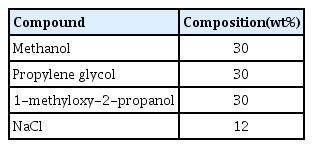

The wastewater used in the study was actual wastewater generated during MC and ECH manufacturing processes. MC wastewater has a high organic matter load of 40,000–60,000 mg/L COD; and its properties are shown in Table 1 [14]. In this study’s preliminary experiments, a foaming problem occurred when MC wastewater was independently treated. The method of mixing ECH wastewater was found to resolve this foaming problem. The ECH wastewater is wastewater from other processes generated during MC manufacturing and has lower salinity and COD concentrations than MC wastewater. The ECH wastewater is characterized by a COD of 150–1,500 mg/L, total nitrogen (TN) N.D., total phosphorus (TP) N.D., and an NaCl concentration of 2,000 mg/L.

2.2. Reactor and Experimental Setup

In this study, a laboratory-scale sequencing batch reactor (SBR) with a 5 L effective volume (length: 155 mm, width: 155 mm, height: 222 mm) was used (Fig. S1). The initial mixed liquor suspended solids (MLSS) concentration was 6,000 mg/L and the seed sludge was dominated by Halomonas spp.. The influent used was a mixture of MC and ECH wastewater, mixed at a ratio of 1 to 9, respectively. The SBR operation consisted of one cycle per day under aerobic conditions, and air was introduced by an air diffuser at the bottom of the reactor with a 2 L/min aeration flow rate. The SBR cycle times were controlled using a programable logic controller (PLC), and each cycle lasted for, with a feeding of 10 min aeration of 23 h and 10 min, settling of 30 min, and a decanting time of 10 min. The total operation period was 108 d, and the hydraulic retention time (HRT) was 2.78 d (exchange rate 36%).

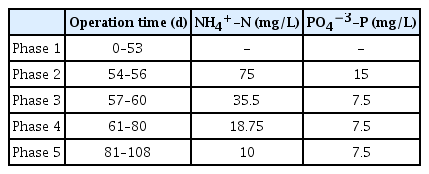

In the initial operation, organic matter removal occurred without the addition of phosphorus and nitrogen. The removal efficiency in this study was less than 80% as the wastewater was nutrient-deficient and required for the biological reaction. To increase removal efficiency, nutrients were administered as shown in Table 2 after 53rd day. The nutrients were used in the following reagents; the nitrogen source being ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, SAMCHUN Chemical, Korea), and the phosphorus source being potassium phosphate (KH2PO4, SAMCHUN Chemical, Korea).

2.3. Analysis of Microbial Community

Changes in the microbial community were observed by pyrosequencing analysis, carried out using the initial and end phases. The supernatant was removed after centrifugation, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted using the FastDNA SPIN Kit for soil (MP Biomedicals). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (C1000 Touch thermal cycler, Bio-Rad) used 2 μL of extracted DNA and proceeded with the primary amplicon and secondary index. In the primary PCR amplicon, the initial denaturation was performed at 95°C for 3 min. After 25 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 30 s), the annealing (55°C, 30 s), extension (72°C, 30 s), and final extension (72°C, 5 min) was conducted and finally fixed at 4°C. In the secondary index PCR, initial denaturation was performed at 95°C for 3 min. After 8 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 30 sec), annealing (55°C, 30 s), extension (72°C, 30 s), final extension (72°C, 5 min) was performed and finally fixed at 4°C. Illumina MiSeq was used for DNA sequencing, and the obtained nucleotide sequence was subsequently analyzed using CLcommunity™ (Chunlab Inc., Seoul, Korea). [27, 28].

2.4. Water Quality Analysis

Water quality analysis was performed with a filtrate using a glass fiber filter (GF/C). In addition, COD, NH4+-N, PO4−3-P, and MLSS were analyzed according to the standard method [29]. The shape of the sludge was observed at 40× magnification using an optical microscope (OLYMPUS CX31).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biological COD Removal

Fig. 1 presents the concentration profiles and the COD removal efficiency in Phase 1. The average COD concentrations of the influent and effluent was 4,400 and 1,300 mg/L, respectively. Removal efficiency was up to 80% over a period of approximately 50 d without the addition of nutrients. Studies of complex chemical wastewater treatment with similar properties obtained a removal efficiency of 50% and 51% [24, 30]. Although Qin et al. [21] confirmed a removal efficiency of 77% of organic matter in the salt (30,000 mg NaCl/L) higher than in this study (13,800 mg NaCl/L), we confirmed a relatively high removal efficiency even in a nutrient-deficient state.

Nitrogen, phosphorus, and external carbon sources should be added because industrial wastewater may lack the nutrients necessary for biological treatment [31]. The ratio of carbon (C) to nitrogen (N) to phosphorus (P) in biological treatment is known to be 100:5:1 [32]. However, the MC wastewater contained no nutrient salts other than the organic compounds, thus the change in COD removal efficiency was confirmed by adding deficiency nutrients (i.e., nitrogen and phosphorus).

Fig. 2 presents the concentration changes in COD, nitrogen, and phosphorus during the operation period. Following nutrient injection, the accumulation of nitrogen and phosphorus occurred because of the excessive nutrients required by microorganisms. As such, the injection of nitrogen and phosphorus in Phase 3 was reduced to half that of Phase 2. In Phase 4, nitrogen injection was reduced to half that of Phase 3, but the accumulation of nitrogen was confirmed. In the next phase, nitrogen had not increased as nitrogen injection had reduced to half of Phase 4.

The profiles of NH4+-N, (a), PO4−3-P, (b), SCODCr, (c) concentration and removal efficiency according to operating condition change (②: phase 2, ③: phase 3, ④: phase 4, ⑤: phase 5).

Ammary [33] showed that the C:N:P ratio was 113:3.3:1 in a similar wastewater treatment study using biological treatment, and the removal efficiency of organic compounds was 75%. In this study, the maximum efficiency in Phase 1 was 80.4%, and increased up to 93.5% through nutrient injection after Phase 2. At that time, the C:N:P ratio was 240:1.3:1 (Phase 5). This indicates that the removal of high concentrations of organic matter may be achieved through the injection of appropriate nutrients.

3.2. MLSS and Sludge Morphology

Fig. 3 shows the change in MLSS and COD removal efficiency. The MLSS concentration increased from 6,000 mg/L to approximately 12,000 mg/L during Phase 1. During Phases 2 to 4, the MLSS concentration gradually increased to 18,000 mg/L. In Phase 5, agitation by aeration was difficult because of the high MLSS concentration, and sludge washout occurred during the effluent (96 d). At that time, the sludge in the reactor had a high proportion of filamentous (Fig. 4(i)), and the suspended solids (SS) of the effluent increased, resulting in a decrease to MLSS to approximately 13,500 mg/L.

Morphology observation of sludge during the operation((a): 3 d, (b): 10 d, (c): 20 d, (d): 31 d, (e): 38 d, (f): 45 d, (g): 62 d, (h): 73 d, (i): 97 d (X40 magnification by optical microscope)).

Studies using biological treatment processes (industrial wastewater: COD 1,000–1,800 mg/L) demonstrate an increase in MLSS of approximately 3,000 mg/L after 2 and 4 months [34, 35]. The results of a study on municipal wastewater (biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) 100 mg/L) confirmed an MLSS increase of approximately 2,000 mg/L after 12 months [36]. However, this study observed a large increase in MLSS, attributed to the higher COD concentration (4,600 mg/L) compared to other studies.

Fig. 4 shows the sludge morphology observed with an optical microscope during the operation period. The sludge was observed to exhibit a granular morphology after the 30th day. The formation of extracellular polymer substances (EPS) by bacteria is known to increase with osmotic pressure with a rise in the salt concentrations of the wastewater [37]. EPS plays an important role in the formation and stabilization of granules by combining bacteria [38, 39]. In addition, Ca+2 is able to bind to negatively charged groups of bacterial surfaces and EPS and act as a bridge to interconnect these components [40], enabling the replacement of Ca+2 by Na+ in highly saline wastewater [41].

The salt concentration of MC+ECH wastewater was 13,800 mg/L, higher than that of other wastewaters. In this study, we confirmed the formation of granular sludge over 1 mm, and the saline condition was favorable for the formation of aerobic granular sludge [42]. In addition, granular sludge formation based on salt condition changes confirmed that an average of 4 mm of granular sludge had formed in salt condition of 40,000 mg/L [43]. Fig. 4(g)–(i) shows that the sludge had a complete granular morphology after the 50th day.

3.3. Microbial Community Analysis

Fig. 5 illustrates the change in the microbial community based on phylum ((a): initial, (b): end). In the Proteobacteria of the great population proportion, (a) and (b) were 59.23% and 40.30%, respectively. In general, Betaproteobacteria in Proteobacteria dominate the microbial community of wastewater treatment systems [44]. However, in this study, the Proteobacteria was dominated by Gammaproteobacteria. The majority of Gammaproteobacteria identified in the study were halophilic microorganisms, in which Gammaproteobacteria dominated saline wastewater treatment systems [45]. The reduction proportion (22%) of Gammaproteobacteria was similar to that of Proteobacteria (19%), which indicates large-scale changes in other halophilic species or phylum (e.g., Chloroflexi, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria).

The dominant phylum in the microbial community changed from Bacteroidetes to Chloroflexi, Actinobacteria etc.. Chloroflexi and Actinobacteria constituted a low proportion of the microbial community at 0.36% and 0.54% in (a), and increased significantly to 26.24% and 16.63% in (b), respectively. Chloroflexi and Actinobacteria belong to filamentous bacteria such as Caldilineaceae and Nocardiaceae, respectively [46, 47]. Filamentous bacteria are known to physically induce binding between bacteria to provide the necessary attraction in the early stages of granulation [48]. Although Chlorobi was not present in (a), it was present at 4.62% in (b). Some microorganisms belonging to the Chlorobi phylum have thermophilic characteristics and are able to decompose compounds such as phthalate esters [49]. The proportion of Rhodothermaeota increased from 2.83% in (a) to 4.02% in (b). It is known that microorganisms belonging to Rhodothermaeota possess thermophilic characteristics and mainly grow in a saline environments similar to seashores [50, 51]. The increase in thermophilic microorganisms is expected to be related to the operating temperature used in this study. The temperature of the discharged MC wastewater was greater than 75°C, and the temperature of the reactor in the actual wastewater treatment plant was approximately 40°C. In our study, it was estimated that an increased proportion of thermophilic microorganisms (e.g., Chlorobi and Rhodothermaeota) was possible as the operating temperature was approximately 35–40°C.

There was a reduction in the proportion of Bacteroidetes, Planctomycetes, Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia, and Tenericutes. Bacteroidetes decreased from 26.53% to 4.03%, and are typically found in various wastewater treatment systems, some of which have halophilic characteristics [44]. Planctomycetes, known as aerobic chemo heterotrophs, decreased slightly from 1.50% to 1.26%; these are mainly found in chemical wastewater treatment [52, 53]. It is estimated that they can grow in halophilic and thermophilic environments. Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia, and Tenericutes decreased from 5.48%, 2.16%, and 0.98% to 0.31%, 0.05%, and 0.01%, respectively. Firmicutes are mainly found in the anaerobic digestion process [54], and Verrucomicrobia has a hydrocarbon hydrolase [55]. They seem to be difficult to grow under the wastewater treatment environment of this study. Altough Tenericutes are also found in various wastewater treatment systems, they exist at a low proportion [56–58] and as such, their contribution is expected to be low.

Fig. 6 shows the pyrosequencing results of Proteobacteria using a dynamic pie chart (Krona) ((a): initial, (b): end). We investigated the Proteobacteria genus to identify microbial characteristics. Halomonas spp. was present in the highest proportion (43.26%) in (a), and has been reported to grow under highly saline conditions, contributing to the treatment of saline wastewater [59]. Though some Alphaproteobacteria, such as Roseinatronobacter spp. (3.45%), Pararhodobacter spp. (2.31%), and Glycocaulis spp. (1.30%), have been found to grow in highly saline environments [60–62], they were not found in (b). Similarly, certain Gammaproteobacteria such as Marinospirillum spp., Aliidiomarina spp., and Alcanivorax spp. are known to be capable of treating highly saline wastewater or soil [63–65]. However, with the exception of Halomonas spp. (0.11%), they were not observed in (b). Marinobacter spp. and Methylophaga spp. constituted 15.12% and 7.51% of the microbial community, respectively, unlike the well-known halophilic microorganisms, Gammaproteobacteria [66–68]. In several studies, the dominant microorganisms in saline wastewater were Halomonas spp., Paenibacillus spp., and Marinobacter spp. [69–72]. We confirmed that Marinobacter spp. and Methylophaga spp. were dominant and are highly biodegradable in a saline environment. Although the seed sludge was dominated by Halomonas spp. growing in high salinity, changes in microbial species appeared due to the wastewater containing methyl groups. Therefore, we estimated that Marinobacter spp. and Methylophaga spp. was dominated by influent. The genera of the sample in the initial and end phases were 297 and 493, respectively, indicating that microbial communities were diverse in the end phase. This may be regarded as an increase in microbial diversity by operating.

4. Conclusions

This study biologically removed the organic matter from highly saline MC wastewater and observed microbial community changes used for biological treatment. The removal efficiency of COD in biological treatment increased from 80.4% to 93.5%, and removal efficiency was improved by the addition of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus to the wastewater. In this case, the ratio of C:N:P was 240:1.3:1. Although the energy and cost consumption in this study was minimal due to the lack of a physicochemical treatment process, it has a limitation requiring the addition of nutrients for high removal efficiency. However, mixing with high concentrations of industrial or municipal wastewater instead of nutrient-deficient ECH wastewater may resolve this requirement to add chemicals, also achieve scale-up.

The sludge was granulated because of the highly saline conditions and the presence of filamentous bacteria. The microbial community in the sludge was dominated by Proteobacteria ((a): 59.23%, (b): 40.30%) in the initial and end phases. There was an increase in the ratio of Chloroflexi ((a): 0.36%, (b): 26.24%) and Actinobacteria ((a): 0.54%, (b): 16.63%), both of which are filamentous bacteria. Proteobacteria was the dominant Halomomas spp. (43.26%), a halophilic microorganism, in (a), whereas Marinobacter spp. (15.12%) and Methylophaga spp. (7.51%) were dominant in (b). In this study, Marinobacter spp. and Methylophaga spp. were dominant, which differs from the results of previous studies whereas Halomonas spp. was dominant in the biological treatment of saline water [73, 74]. Therefore, we expected Marinobacter spp. and Methylophaga spp. to contribute to the biological treatment of MC wastewater.

This study revealed that Marinobacter spp. and Methylophaga spp. contribute to the treatment of MC wastewater, and confirmed that the addition of nutrients is necessary. Through, this study provided information on MC wastewater treatment that was not previously studied, and contributed to the development of industrial wastewater treatment.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgment

This subject is supported by Korea Ministry of Environment as “Global Top Project” (Project No.:2016002190006).

Notes

Author Contributions

G.S.J. (M.S. student) conducted all the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.W.H. (Ph.D. student) conducted all the experiments and revised the manuscript. H.G.K. (Ph.D.) revised the manuscript. Z.L.P. (Professor) revised the manuscript. D.H.A. (Professor) revised the manuscript.