Spatiotemporal variations and source apportionment of NOx, SO2, and O3 emissions around heavily industrial locality

Article information

Abstract

The main objective of this study is to estimate the levels of pollution to which the community is presently exposed and to model the regimes of local air quality. Diurnal, daily, and monthly variations of NO, NO2, SO2, and O3 were thoroughly investigated in three areas; namely, residential, industrial, and terminal in Ras Al-Khafji. There is obvious diurnal variation in the concentration of these pollutants that clearly follows the diurnal variation of atmospheric temperature and main anthropogenic and industrial activities. Correlation analysis showed that meteorological conditions play a vital role in shaping the pattern and transportation of air pollutants and photochemical processes affecting O3 formation and destruction. Bivariate polar plots, an effective graphical tool that utilizes air pollutant concentrations’ dependence on wind speed and wind direction, were used to identify prevailing emission sources. Non-buoyant ground-level sources like domestic heating and street transport emissions, various industrial stacks, and airport-related activities were considered dominant emission sources in observatory sites. This study offers valuable and detailed information on the status of air quality, which has considerable, quantifiable, and important public health benefits.

1. Introduction

Air pollution has been a major threat for decades, and its harmful impacts have attracted attention from environmental health researchers, international environmental regulatory agencies, and even the public. Several previous and recent studies have reported various health outcomes caused by air pollutants. These include nose and throat irritation [1, 2], lung inflammation [3], ischemic stroke [4], autism [5], schizophrenia [6], and depression [7]. Concerns have been augmented not only in developed countries, but also in developing countries as a result of dramatic population growth, massive energy consumption, and rapid urbanization. Therefore, investigating the level and pattern of air pollutants (and their spatial and temporal variations) and allocating their potential emissions sources are key parts of any air quality management program.

Numerous studies focused on the spatial and temporal variations of primary (SO2, PM10, NO2, and CO) and secondary (O3) air pollutants [8–12]. Substantial seasonal differences and long-term trends of air pollutant levels have been noticed in several regions around the world [9–10, 13–16]. Seasonal and trend disparities among cities could be due to several factors including the spreading of local pollution sources, the existence of distant pollution sources that influence the city, and the meteorological and topographical conditions of the area [17–18].

Various atmospheric reactions, induced by primary pollutants, are leading to different air pollution episodes. The atmospheric transformation of SO2 and NO2 to particulate sulphate and nitrate is at the center of urban photochemical reactions [19–20]. Additionally, the resultant sulphate and nitrate are basic constituents of nitric and sulfuric acids, which in turn lead to a decrease in visibility, the acidification of soil and water, and an escalation of respiratory diseases among the human population [20]. Furthermore, a close association was found between the ground-level ozone O3 and other photochemicals and increases in particulate matter (PM10) in the atmosphere [21–22].

The fate of air pollution episodes depends on several factors including intricacy of emissions sources and intensity, topography and the local situation [23], solar radiation intensity, and meteorological conditions. Ghazali et al. [24] reported that differences in O3 amounts are positively associated with temperature: lower temperatures lead to an increase in polar stratospheric clouds and a reduction in ozone levels. Tan et al. [25] attributed the accumulation of toluene in haze days to lower wind speed, weaker air convection, and weaker atmospheric diffusion. Abdul-Wahab et al. [26] revealed, through stepwise multiple regression analysis, that high levels of daytime O3 concentrations are ascribed to solar levels, whereas at night NO2 was the main driver. Hussein et al. [27] speculated that temperature inversion induces O3 formations.

Air pollutant monitoring studies are of great importance as they induce air quality management efforts, assess potential combined effects, allocate the likely emission sources, determine the short and long pollution transport, and improve air quality control regulations [28–30]. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the spatiaotemporal variations, statistical distributions, and prevailing emission sources of air pollutants (with special emphasis paid to NO, NO2, SO2, and O3) around densely populated industrial locations near residential areas in Al Khafji City in Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Area of the Study

This study explores the air quality status in Ras Al-Khafji, a town near the southern border with Kuwait in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Fig. S1). It is located in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Region along the Arabian Gulf. The city is situated between latitude 28–26 N and longitude 48–30 E. It is 10 km south of the Saudi-Kuwaiti border, 130 km south of Kuwait City, and 300 km north of Dammam. Ras Al-Khafji encompasses a residential area (which includes commercial activities), a terminal area (KJO Heliport), and an industrial area. The industrial area serves as the base of the Kuwait Oil Gulf Company (KGOC), which is managed jointly by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia for oil and gas exploration. The population of Khafji is approximately 65,000. A significant proportion of the population is composed of oil company employees and their families, and thus a large proportion of residents came to Khafji from different cities in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

Al-Khafji has an arid climate, with a total average annual precipitation of 105 mm. The quantity of annual precipitation substantially varies from one year to another, with some years witnessing over 200 mm of precipitation while others see only a few millimeters. The average springtime temperature is 21°C with relative humidity of about 50%. In the summertime, the temperature averages around 33°C with relative humidity of about 50%. Autumn sees average temperatures around 29°C with relative humidity of about 50%. The climate in Al-Khafji is typically arid with very hot summers and relatively cold winters. The summer season in Al-Khafji falls between May and September, the winter season between November and March. Temperatures in the summer can exceed 50°C, and in January, the coldest month, temperatures range from 0°C (inland desert areas) to 20°C (coastal areas).

Regarding source emission in Al-Khafji City, there are three flare stacks and 19 other stacks at the combustion facilities, which include (i) the seawater desalination plants, (ii) the power plant, and (iii) the production facilities. The three flare stacks flare sweet and sour gases. Additionally, there are two stacks for the two boilers at the Saline Water Conversion Corporation (SWCC) plant, which is considered the only major non-KJO emission source in Al-Khafji city.

2.2. Data Description and Analysis

In the current study, NO, NO2, SO2, and O3 were measured by Environment & Laboratory Department (ELD) at Al-Khafji Joint Operations (KJO). ELD operates and maintains air quality monitoring and meteorology stations. The pollutants of interest were measured by air quality monitoring stations using HORIBA analyzers. The ambient air pollution analyzers feature advanced technology, field-proven reliability with excellent sensitivity & precision at ppb levels, and hassle-free maintenance. Each of these monitors differs in their operation principle and measures single/multiple components in ambient air. The technical specifications of ambient air quality monitoring analyzers are listed in Table S1.

Three monitoring stations at different locations were used in this study to evaluate the air quality. The first monitoring station was located in the residential area, the second in the industrial area, and the third in the heliport area. The locations of each monitoring station are shown in Fig. S1. The locations of these air monitoring stations were selected based on the air dispersion modeling results with respect to the applicable site selection criteria, with particular reference to the monitoring objectives and practical considerations.

Meteorological conditions data, such as wind speed (m/s) and direction, corresponding to collected air pollutants were also measured. A wind rose of the average wind direction monitored in the Al-Khafji area during 2012 (the study period) is shown in Fig. 1, which reflects the natural direction of prevailing winds for the Khafji area, which is mostly northwest and southeast. In order to assess the air quality in Al-Khafji, measured levels of air pollutants were compared with threshold limits specified in the rules and regulations of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Presidency of Meteorology and Environment (Table S2).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Measures of central tendency, frequency analysis, and correlation analysis were obtained using the statistical package Statistica. Correlations between air pollutants and meteorological parameters were tested using the Pearson coefficients. One-way ANOVA analysis was employed to detect the differences between sites regarding diurnal and seasonal variations. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be of statistical significance. Normality of air pollutants was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Statistical Software R programming language, with package openair version 2.13.2 [31], was used for other statistical tests and making graphs.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Level, Pattern, and Impacts of Air Pollutants

3.1.1. Nitrogen oxides

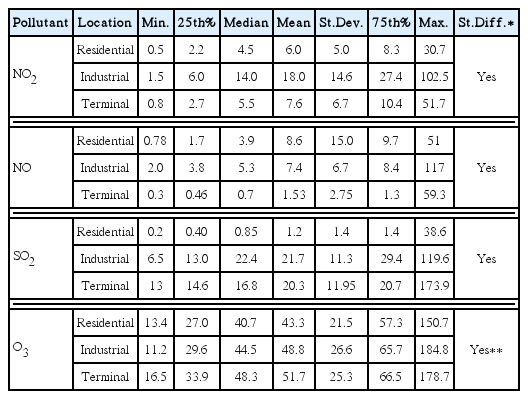

Characteristics of nitrogen oxides (specifically NO and NO2) in different localities (namely residential, industrial, and terminal sites) were thoroughly investigated; their descriptive statistics during the entire year of 2013 are listed in Table 1. The NO2 concentrations ranged from 0.5 to 30.7 ppbV, 1.5 to 102.5 ppbV, and 0.8 to 51.7 ppbV, with averages of 6 ± 5 (SD) ppbV, 18 ± 14.6 ppbV, and 7.6 ± 6.7 ppbV, in residential, industrial, and terminal sites, respectively. One-way ANOVA analysis showed a significant variation (p-value < 0.5) among the three different locations. NO emissions patterns were similar to those observed with NO2 with slight differences in amplitudes (Table 1). Nitrogen oxides, specifically NO and NO2, are well recognized as a product of the fossil fuel combustion process. In traffic areas, the emissions are mostly NO, which is readily converted through atmospheric photochemical reactions to NO2, which is a key precursor of ozone formation [32–33]. The level of nitrogen oxides in the industrial area was higher than those in the residential and terminal sites, which is to be expected. This is due to various combustion activities in industrial areas, such as seawater desalination plants, power plants, and oil production facilities.

Monthly variations of NO and NO2 in the three different sites were also investigated (Fig. 2). A wide distribution of NO and NO2 concentrations was observed, as shown in box plot analysis (Fig. 2), especially in the residential area where NO and NO2 emissions are driven by traffic. In industrial and terminal locations, there were monthly variations in NO and NO2 emissions, but fewer than those noted in the residential area, as combustion activities are somewhat fixed over the year. Overall, the levels of NO and NO2 increase in the winter months, which is congruent with previous studies [12, 34] where in cooler months solar radiation intensity decreases and thus the extent of photochemical reactions reduces NO/NO2 destruction. Differences in the magnitude of monthly NO and NO2 emissions among residential, industrial, and terminal sites were significant (p-value < 0.5), highest in the industrial area. In terms of exceedances, all NO and NO2 values were below PME permissible values.

Boxplot analysis of NO2, NO, SO2, and O3 concentrations at (a) residential, (b) industrial, and (c) terminal areas.

From a health perspective, higher levels of NO2 cause reductions in pulmonary functions. This reduction induces an inflammatory reaction on the surfaces of the lung [35] and leads to morbidity and mortality [36]. These effects are of more concern in young children, asthmatics, and those with chronic bronchitis and related conditions [37].

3.1.2. Sulfur dioxides

Sulfur dioxide concentrations were also studied; their descriptive statistics are listed in Table 1. The SO2 concentrations varied from 0.2 to 38.6 ppbV, 6.5 to 119.6 ppbV, and 13 to 173.9 ppbV, with averages of 1.2 ± 1.4 (SD) ppbV, 21.7 ± 11.3 ppbV, and 20.3 ± 11.95 ppbV, in residential, industrial, and terminal sites, respectively. No differences were detected between the industrial and terminal areas, indicating similar prevailing emission sources in those two areas. However, significant differences were found between the former two areas and residential areas (p-value < 0.5). SO2 is released into the atmosphere primarily from anthropogenic activities such as the combustion of sulfur-containing fossil fuel [38–39]. Over the past two decades, there has been a great reduction in the sulfur content of gasoline and diesel fuel, which has reduced the contribution of automobiles to atmospheric emission of SO2. This could possibly explain the low levels of SO2 that were measured in residential areas (that were labeled as traffic areas) in this study. Although various abatement technologies are used in many industries to mitigate SO2 emissions, the numerous combined point sources can release a significantly high concentration of SO2 into the atmosphere. This could explain the higher levels of SO2 in the industrial area in this study compared to the residential area. SO2 is oxidized by OH radicals in the gas phase and by O3 and H2O2 in the aqueous phase to form acid deposition, which can pose a serious risk to vegetation and aquatic life in ecologically sensitive areas [40].

The monthly patterns of SO2 in the three different sites were also studied (Fig. 2). The distribution ranges of SO2 concentrations within each month were wide over the entire year in all three monitored areas (Fig. 2). The distribution ranges displayed for SO2 in the residential area were narrower than those observed in both the terminal and industrial areas. In terms of monthly variation, there were slight variations in SO2 levels in both the residential and terminal areas, while clear variations were observed in the industrial area. In all monitored areas, the SO2 emissions in the winter months were slightly higher than in the summer months. The increased levels of SO2 in the winter months could be attributed to the combined effects of anthropogenic sources and natural sinks under certain meteorological conditions that were encountered during the course of the study.

SO2 is responsible for various health consequences including emergency hospital admissions for respiratory problems and chronic pulmonary disease at lower levels of exposure and mortality (total, cardiovascular, and respiratory) at higher exposure levels [41–43]. Additionally, an association between SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome) and daily concentrations of air pollutants has been reported in 12 Canadian cities [44]. The study demonstrated that atmospheric SO2 and NO2 might be important risk factors for SIDS. Although SO2 values at all monitoring stations in this study were below the regulatory values stipulated by PME, the combined effects of air pollutants are inevitable.

3.1.3. Ground ozone

Descriptive statistics of hourly ground-level ozone (O3) concentrations in the residential, industrial, and terminal sites are listed in Table 1. The O3 concentrations fluctuated from 13.4 to 150.7 ppbV, 11.2 to 184.8 ppbV, and 16.5 to 178.7 ppbV, with averages of 43.3 ± 21.5 (SD) ppbV, 48.8 ± 26.6 ppbV, and 51.7 ± 25.3 ppbV, in the residential, industrial, and terminal sites, respectively. In terms of statistical differences, the changes in O3 magnitude between residential and industrial and between residential and terminal are statically significant (ANOVA, p-value < 0.5). The ground-level O3 is a secondary pollutant, produced through complex photochemical reactions in the presence of sunlight, NOx, and precursor VOCs [45–46]. The differences in NO/NO2 in these three areas (Table 1) and other ozone formation precursors such as VOCs possibly induced the changes observed in O3 levels among the three areas. Although NO and NO2 level in terminal area were smaller than those observed in industrial area, O3 level was high plausibly due to the increased level of BTEX, aromatic-VOCs, (8.65 ± 1.6 (SD) ppbV) compared with both industrial (4.45 ± 1.5 (SD) ppbV) and residential areas(3.26 ± 1.2 (SD) ppbV); Table S3. An elevated O3 level in terminal area is attributed to the presence of fueling station for helicopters in this area. Previous studies demonstrated that VOCs play a key role in tropospheric O3 formation. Li et al. [47] reported fluctuation of 5–25 ppb in O3 with variation of VOCs emission in Houston area. Filella and Penuelas [48] highlighted that VOCs has substantial biogenic component, which has a significant impacts in O3 formation.

Levels of O3 were also investigated on a monthly basis (box plot analysis is shown in Fig. 2). The O3 levels exhibit similar patterns in the three tested areas: increases in the summer months (May-September) and decreases in the winter months, contrasting those of NOx and SO2. The increased levels of O3 in the summer months in this study are consistent with previous studies [49–51]. Such a phenomenon was plausibly demonstrated by the dominant photochemical production process of O3 due to the high intensity of solar radiation and the existence of NOx and other O3 precursors during the summer.

Exposure to O3 is associated with various detrimental health impacts, as reported by several meta-analyses worldwide. In one study [52], it was reported that an increase of 10 μg/m3 in O3 led to a 0.87% increase in all-cause mortality and a 1.11% increase in cardiovascular diseases. Additionally, a meta-analysis on 95 urban communities in the U.S. showed that an increase of 20 μg/m3 of O3 would lead to a 0.52% increase in total mortality and a 0.64% increase in cardiovascular and respiratory mortality [53]; another study [54] reported a rise in all-cause mortality with a 0.39% increase (95% CI 0.26–0.51). It was also reported that exposure to O3 can cause chromosomal damage [55]. In this study, few exceedances were observed for O3 in all monitoring stations from April to October, which would need to be controlled to avoid any potential health risks.

3.2. Frequency and Correlation Analysis

The frequency distributions of NO, NO2, SO2, and O3 were evaluated in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas to discover the occurrence patterns of their pollution. Frequency distributions of NO2 are shown in Fig. 3. NO2 frequency distributions in all three areas were closely correlated with a log-normal distribution. Log-normal distribution was most frequently proposed for ambient air quality data [56] and indoor air pollutants [57]. The frequency distributions exhibited distinct skewness with an extended tail at high values, with positive skewness coefficients of 1.5, 1.0, and 1.7 ppbV in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas, respectively. Kurtosis coefficients, which measure the peakedness of a distribution, were 2.2, 0.53, and 3.6 ppbV in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas, respectively, which indicate a flatter shape than normal. NO2 maximum concentrations were observed within 0–2.5 ppbV, 0–10 ppbV, and 0–5 ppbV intervals in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas, respectively. NO distributions, which are strongly and positively skewed with coefficients at least four times higher than those observed with NO2, exhibited strong compatibility with each other. The occurrences of the peak concentrations converge most commonly in concentration ranges of 0–25 ppbV, 0–10 ppbV, and 0–5 ppbV in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas, respectively. High kurtosis coefficients were observed (61.6, 27.7, and 77.3 ppbV in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas, respectively), which indicate higher, sharper peaks and that more of the variability is due to a few extreme differences from the mean. Unlike NOx, disparities were observed in SO2 frequency distributions among the three tested areas (Fig. 3). Skewness and kurtosis values in the residential area (8.9, 163.4 ppbV) were positive and significantly higher than those observed in the industrial (1.5, 7.3 ppbV) and terminal (3.9, 22.5 ppbV) areas, which means that the frequency distribution extends to high SO2 values with a sharper peak. A peak in the SO2 distribution occurred most frequently within the ranges of 0–2.5 ppbV, 20–30 ppbV, and 10–20 ppbV in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas, respectively. The distribution patterns of O3 were also investigated and are shown in Fig. 3. The distributions in all three of the tested areas have a similar shape. Both skewness and kurtosis values in the residential (0.67, 0.41 ppbV), industrial (0.8, 0.87 ppbV) and terminal (0.8, 0.96 ppbV) areas are approaching zero, which shows that the data are approximately symmetric and that distributions can be fitted by normal distribution. These observations were also confirmed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which suggested a normal distribution (p < 0.01). It should be noted that all frequency distribution profiles (Fig. 3) were single-peaked, which indicates that the sources for NO, NO2, SO2, and O3 at the monitoring sites were relatively few.

Frequency distribution of NO2, NO, SO2, and O3 concentrations at (a) residential, (b) industrial, and (c) terminal areas.

Correlation analysis was performed to further investigate the relationship between air pollutants and meteorological conditions in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas (Fig. 4). Interestingly, Pearson’s correlation matrices (Fig. 4) exhibit similar patterns and dependencies in the three different tested areas. Data show positive correlation coefficients between NO, NO2, and SO2, with high correlation coefficients between NO and NO2 (r = 0.53–0.73), indicating that these pollutants originate from similar sources. O3 concentrations were negatively correlated with NO, NO2, and SO2. This finding is consistent with previous studies that reported that these pollutants have been recognized as O3 precursors in addition to VOCs [26, 58–60]. Meteorological conditions also play a vital role in photochemical processes affecting O3 formation and destruction. Wind speed was positively correlated with O3 possibly due to its transportation, although there were some discrepancies in the residential area that may have been due to the transport of NO, NO2, and SO2, which are all O3 precursors. Negative correlations were also observed between wind speed and NO, NO2, and SO2, demonstrating dilution of these air pollutants by wind.

3.3. Temporal Variation

Temporal variations (diurnal, weekly, and monthly) of NO2, SO2, and O3 are measured on an hourly basis and modeled in the residential, industrial, and terminal sites, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Data are presented in normalized levels for ease of displaying pollutants with different scales in the same plot. The diurnal pattern of NO2 in the residential area (Fig. 5(a)) showed two peaks (one at 6:00 am, begun at 3:00 am and then diluted between 10:00–13:00), while the second peak commenced at 15:00 pm and reached maxima at around 20:00 pm. The diurnal patterns of NO2 in the industrial and terminal areas (Fig. 5(b) and (c)) are similar to those observed in the residential area, but with different amplitudes, indicating similar prevailing sources. NOx peaks at two time slots that coincide with rush-hour traffic, which could be one of the dominant sources in addition to various industrial activities in these observatory sites. NO followed a pattern similar to NO2 and therefore the data were not shown for the sake of brevity. The diurnal pattern of SO2 exhibited the same pattern as NO2 with slight shift (~1–2 h) ahead. It was reported that heating plants and domestic heating, vehicle-fuel combustion, and fossil fuel combustion from industrial activities are the main anthropogenic sources of NO2 and SO2 emissions in urban areas [61]. The O3 diurnal patterns in all three observatory sites in this study were almost identical. The peak commenced during early morning (~4:00–7:00 am) and steadily increased to its highest peak at 13:00 pm. The high O3 levels lasted until 15:00 pm and then decreased speedily until midnight and early morning hours; this trend continued the next day. As stated earlier, O3 concentrations were negatively correlated with NO, NO2, and SO2, indicating that these pollutants are considered O3 for mation precursors. Abdul-Wahab et al. [26] found that solar levels contributed considerably to elevated daytime O3 concentrations with NO, whereas NO2 was the major stimulus at night. Additionally, the contribution of temperature inversions, a feature that is common in urban areas, to formation cannot be ruled out [27]. In terms of monthly variations, NO2, SO2, and O3 emissions showed distinct monthly patterns: lower during the winter season, while the higher concentrations were experienced during the summer (from May to July). The average temperature in Al-Khafji City, where the three observatory areas are located, is highest (42–48°C) from May to July. These higher temperatures are characterized by peak energy consumption months, leading to higher NO2 and SO2 levels, emissions, and photochemical production. Regarding weekday emission patterns, the variations are alike at all tested sites; there is no sign of a weekday change in emissions or concentrations.

3.4. Source Apportionment

Bivariate polar plots are a valuable graphical tool for discerning different source types and characteristics [62–63]. These plots dema onstrate the variation of air pollutant concentrations with respect to wind speed and direction. Polar coordinates enhance the knowledge about directional dependence of different sources, mostly once multiple observing sites are investigated [64], as was the case in this study.

Fig. 6(a) shows bivariate polar plots for NO2 (left) and SO2 (right) in the residential areas. In the residential area, NO2 was highest (~3–5 ppb) at low-moderate wind speed (2–4 m/s) from the north and northwest. The prevailing NO2 emission source from the north is residential activities, where most houses are, and from the northwest corresponding to a busy main road. The elevated levels transpire under stable atmospheric conditions when non-buoyant ground-level sources like domestic heating and street transport emissions are significant [65]. SO2 in the residential area exhibited high concentrations from all wind directions, but was progressive towards the northeast and northwest. Unlike NO2, the highest levels of SO2 were observed under high wind speeds (up to 8 m/s), which indicates contribution of industrial stacks instead of non-buoyant ground-level sources as observed with NO2 polar plots. The industrial area lies southeast of this residential area (distance ~ 3.41 km) and the wind in the industrial area blows 8–16% of the time from the southeast (Fig. 1(b)), leading to a transferring of SO2 emissions toward the residential area observatory site. The contribution of transportation to SO2 emissions should be eliminated. There have already been tremendous efforts to reduce the sulfur content in diesel and gasoline fuels nowadays, along with the equipping of vehicular tailpipe technologies like NSR and SCR technologies [66–67].

Bivariate polar plots of NO2 and SO2 concentrations at (a) residential, (b) industrial, and (c) terminal areas.

Fig. 6(b) shows bivariate polar plots for NO2 and SO2 in the industrial area. In contrast to the residential area NO2 emissions, high NO2 concentrations (20–30 ppb) in the industrial area were observed from all directions, with increases from the northwest. Bivariate polar plots for SO2 are almost identical to those for NO2, demonstrating similar prevailing sources. Elevated NO2 and SO2 concentrations in the industrial observatory site were observed under high wind speeds (up to 12 m/s), signifying that NO2 and SO2 originate from stack emissions. The observatory site in the industrial area is indeed surrounded by numerous stack emissions including the power plant, oil production facilities, and seawater desalination plants.

Bivariate polar plots for NO2 and SO2 in the terminal area are shown in Fig. 6(c). The highest concentration of NO2 was observed from the northeast at low-moderate wind speed (2–5 m/s). Elevated NO2 levels originated from more stable atmospheric conditions and reduced advection associated with low wind speed, but did not diminish the contribution of stack emissions. This observatory site is bounded by Al-Khafji Airport on the west side, an airport road on the east, and industrial activities (~2.54 km) on the northeast side. Polar plots for SO2 show the highest concentrations (24–28 ppb) from the northeast under high wind speeds (up to 10 m/s) and highlight that industrial stacks are the dominant source type at this monitoring site.

3.5. Seasonal Daytime/Nighttime Variation of Ozone

Unlike primary pollutants (e.g., NOx and SO2), O3 does not come directly from identifiable combustion sources; instead it is formed in the atmosphere. To gain more insights about dynamic changes of ozone, the data were split into different seasons of the year and different times of day (day or night) along with their percentile levels (percentile rose). This is a powerful technique that shows the distribution of O3 by wind direction and can give useful information about different emission sources, like those that only influence high percentile concentrations such as a chimney stack [31, 68]. Seasonal average daytime and nighttime concentrations of O3 in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas are shown in Fig. 7. In the residential area (Fig. 7(a)), O3 levels were higher in the spring and summer and when they were dominated by southeast and northeast winds, followed by autumn and winter during daylight. The patterns of O3 levels during nighttime were the opposite of those observed at daylight: they were higher in the winter and autumn followed by spring and summer when the wind was from the southeast. In the industrial area (Fig. 7(b)), O3 concentrations (both daytime and nighttime) were higher than those observed in the residential area, which was expected since various emission activities take place in the area. Again, high O3 concentrations (greater than the 95th percentile of all observations) at daylight were found in the spring and summer followed by winter and autumn, but they were dominated by northwesterly wind directions (~13–25% of time) and southeasterly wind directions (~8–16% of time). The pattern and distribution of seasonal average daytime and nighttime concentrations of O3 in the terminal area were similar to those noticed in the residential area (Fig 7(c)), but with magnitudes comparable to those observed in the industrial area. The prevailing emission source of O3 in the residential, industrial, and terminal areas is the emission of ozone-precursor pollutants like NOx and SO2, as discussed in section 3.5.

A percentile rose plot of O3 concentrations at (a) residential, (b) industrial, and (c) terminal areas. The percentile intervals are shaded and are shown by wind direction. The plot shows the variation by season and whether it is nighttime or daylight hour.

Higher levels of O3 were observed during daylight and in the summer season in all three tested areas (residential, industrial, and terminal). This can be attributed mainly to photo-oxidation of industrial and anthropogenic pollutants (e.g., NOx, SO2, and hydrocarbons) [69–71]. In the early morning hours during sunrise, the level of O3 progressively increases and reaches maxima at 14:00 pm (Fig. 6) due to high intensity of solar radiation through the photolysis of NO2 [72]:

Where M denotes a collision partner not affected by the reaction.

In the three observatory areas, the average temperature is highest (42–48°C) during between May and July, leading to higher photochemical production. The decreased level of O3 during the nighttime (which starts to decrease after 16:00, Fig. 5) is ascribed to the absence of photolysis of NO2 and loss of O3 by NO via titration reaction and surface deposition [71].

Seasonal variations in O3 levels were observed in three monitored areas. This is likely due to different meteorological conditions, dominant industrial and anthropogenic pollutant emission sources, and traffic patterns and density [73].

4. Conclusions

The current study provides a comprehensive picture of the status of air quality within the borders of the KGOC, which determines public health benefits. Data show positive correlation coefficients between NO, NO2, and SO2, whereas O3 concentrations were negatively correlated with these pollutants. Negative correlations were also observed between wind speed and NO, NO2, and SO2, demonstrating dilution of these air pollutants by wind, while wind speed was positively correlated with O3 possibly due to its transportation. In terms of diurnal variation of NOx, SO2, and O3, there is clear variation in the level of pollutant concentration, which obviously follows the diurnal variation of atmospheric temperature and main anthropogenic and industrial activities. NO2, SO2, and O3 emissions showed distinct monthly patterns (lower during the winter season and higher during the summer). The average temperature during summer in Al-Khafji City is highest (42–48°C) between May and July. Elevated temperatures are characterized by peak energy consumption months, leading to higher NO2 and SO2 emissions and photochemical production. Regarding weekday emission patterns, the variations are alike in all tested sites; there is no signal of a weekday change in emissions or concentrations. Elevated concentrations of O3 during daylight and in summer were ascribed to photo-oxidation of industrial and anthropogenic pollutants (e.g., NOx, SO2, and hydrocarbons). The decreased concentration of O3 during the nighttime may be attributed to the absence of photolysis of NO2 and loss of O3 by NO via titration reaction and surface deposition. Bivariate polar plots consider non-buoyant ground-level sources such as domestic heating and street transport emissions, various industrial stacks, and airport-related activities as prevailing emission sources in observatory sites.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kuwait University for supporting the completion of this study.